Story of a President

His international experience as coach gave shape to the revolution that Luis Puig intended to take on the Spanish cycling. In his first appearance at the Giro d’Italia was fascinated: “Rhythm, speed, position in the peloton, fans like arrows and equipment operation. Teams with a sprinter, two climbers and a champion, a true team leader and the other domestic ones, headed to work. It was what I intended to impose.”

The cyclist´s subordination of work to team orders became an obsession for the coach. His plans, however, clashed with the strong rivalry among the top two Spanish cyclists of the time, Federico Martin Bahamontes and Jesús Loroño, a rivalry also fueled by partisan pressure from their sponsors and the press, which prevented establishing a common tactic for the benefit of group. The conflict erupted in the “Vuelta España” in 1957.

The golden age of Spanish cycling was beginning to take shape. El Correo Español-El Pueblo Vasco had assumed the organization of the “Vuelta España” in 1955, after five years without celebrating it. In 1957, Bahamontes and Loroño headed the Spanish team led by Puig, convinced that the development of the final competition would appoint a team leader: “In this duo of monsters of cycling I have to coordinate what it cannot be coordinated.”

The “Vuelta España” arrived in Valencia with Bahamontes as the leader. Bernardo Ruiz, who knew the tramontana of Perelló, launched an attack to which Loroño responded, dissatisfied with the leadership of the Águila of Toledo. Although Puig had initially ordered the Basque cyclist not to cooperate with the break, when the advantage was of around fifteen minutes, he required him to put his back into it. The French team was confident that Bahamontes would jump to his rival and make the work to his team leader, Raphael Geminiani, but Ruiz and Loroño reached Tortosa’s goal with 21 minutes of advantage.

Loroño took the leader´s jersey to Bahamontes and the French Geminiani was ruled to fight for the final victory. “The Spanish team had won the first and second place overall. It had been a perfect move for me, no matter the name.” The commotion woke the pressure of the godfathers of these two figures of the bunch: Francisco Ubieta, from Loroño, and Manuel Serdán from Bahamontes. Puig met the team at their hotel and cut off all the external communication with brokers. “It is a success and we are a team.”

From that meeting emerged the so-called Pact of Huesca. The strategy envisaged that Bahamontes attacked on the last climb to sentence the lead of the mountain and the second place overall. Then he would rejoin the squad. The moment arrived and the one from Toledo attacked, but Loroño, suspicious, jumped after him. Puig came after with the car: “Jesus! Back! “No, I do not trust him to stop,” replied the one from Vizcaya. Then he went forward to the front of the stage to call for calm at Federico, who had angered: “He is coming after me, he is attacking me. There is no agreement, I do not stop up there.”

After crowning the port, Bahamontes began a downward spiral with Loroño´s leadership in the spotlight. However, Luis Puig did not hesitate to use any means at his disposal for their brokers to obey his team orders. He ordered the driver of the organization´s Land Rover from which he followed the stages to obstruct Bahamontesin the descent, side to side of the road, until he got him reintegrated in the bunch.

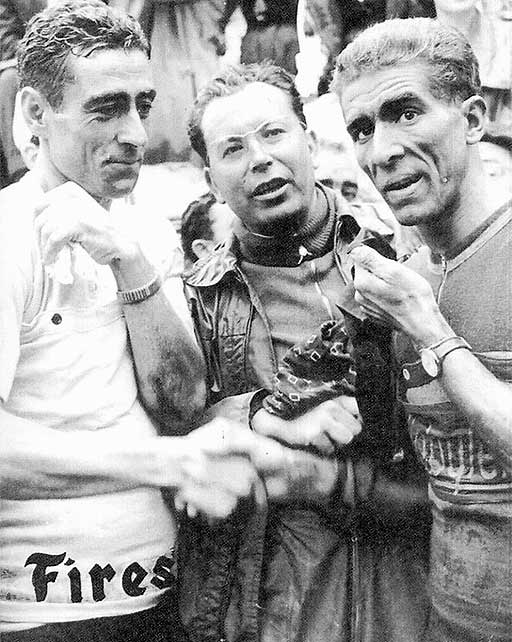

Loroño’s win in the ultimate goal of Bilbao on the podium along with Bahamontes and Bernardo Ruiz, represented, in the words of Luis Puig, a historic turning point for the Spanish cycling: “First working and subordination lesson in the team. Nowadays everyone understands it, but at that time it meant a revolution.”